Cade Cunningham is a star. To become a superstar, he'll have to fix two problems

Cade Cunningham is having a moment. But how high can he soar with two distinct weights dragging him back down to Earth?

In his fourth season (and first with a dedicated, competent NBA coach in JB Bickerstaff), the 6’6” point guard is putting up All-Star numbers: 23.6 points, 9.3 assists (third in the NBA!), and 7.3 rebounds per game on 45% shooting from the field. He’s also canning 38% of his 6.3 three-balls per game.

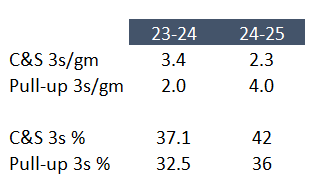

Cunningham’s most notable improvement is in his shot. The three-pointer was a major question mark for Cade coming into the year, but he’s shooting a career-high on both accuracy and volume, and it’s become a legitimate weapon. Importantly, the improvement has come across the board and supported a shift in how the shots are generated:

Looking at that exquisitely designed chart, we see several noteworthy things. First, you’ll see his percentages have improved substantially and roughly equally on both catch-and-shoots and pull-ups, a fantastic indicator of his versatility. Second, you’ll notice that Cunningham has shifted more toward pull-ups (a harder shot by nature).

This is unusual! We often hear that coaches want star guards to take more catch-and-shoots because, for most players (including Cade), that’s the more efficient shot. The gravity of a team’s biggest star moving off-ball can free things up for lesser heavenly bodies, too. But Cunningham is doing far more self-made magic off the dribble than before and converting it at a very respectable rate.

In fact, that’s an overall trend in Motown: the Pistons are quickly resembling the kind of heliocentric offenses that have started to fall out of favor.

Everything flows through Cunningham. He is third in the league with 94.5 touches per game, the same number as Trae Young and more than LaMelo Ball, Giannis Antetokounmpo, or Luka Doncic. He’s sixth in passes per game, and his 34.9% usage rate is fifth behind only Ball, Giannis, Ja Morant, and Shai Gilgeous-Alexander.

Despite the gaudy assist totals, I’m not sure Cunningham’s passing has improved so much as the team’s offensive personnel has (it must be nice to play with some veterans like Malik Beasley who are capable of making the occasional shot, although the team’s shooting is still lackluster overall). Dishing remains Cunningham’s best attribute. He has especially nice vision finding alleys for oops:

Cunningham is attacking the boards with a renewed vigor this season (personal aside: I love rebounding guards), and his defensive effort has dramatically improved from last season’s career-worst level. Coach Bickerstaff has always gotten the best from his players on that end, and Cunningham is no exception. He’s had some loud blocks, both of the chase-down variety and as the low-man help defender. This one on Antetokounmpo (followed by a sexy long-range bounce pass) deserved a comic-book-style “POW!”:

Bickerstaff hasn’t shied away from siccing Cunningham on talented ballhandlers, either. He’s been the primary defender on Jaylen Brown and Jalen Brunson, for two notable examples. While defensive tracking data is suspect at best, opponents have shot 4.2% worse than expected with Cunningham as the nearest defender (in the same neighborhood as Dillon Brooks, Draymond Green, and Evan Mobley, although I’m certainly not suggesting he’s on their level as a defender).

At this point, Cunningham is a bit too slow and inconsistent to be more than an average defender, but average is fine! He’s rarely the weak point offenses will attack — teams have only targeted him 13 times in isolation, far less on a per-game basis than last year. They prefer to go after juicier targets like Tim Hardaway Jr. or Tobias Harris (although Harris, in particular, has held up well in those situations). It is worth noting that Bickerstaff’s players have historically shown steady growth across multiple seasons. Cunningham’s size and intelligence mean he could end up being a plus on that end.

Add it all up, and he’s carrying a two-ton made-in-Detroit SUV on his shoulders. It’s a heavy load for a fourth-year player, particularly one still with fewer than two full seasons of games under his belt. To Cunningham’s immense credit, he’s grown with his burden. His advanced metrics are at career-best levels, including an EPM just outside the top decile of the league. Andy Bailey’s Huge Nerd Index, which averages seven prominent catch-all metrics, rates him as the 30th-best player in the league. Having turned 23 the day before Halloween, Cunningham is younger than every single player above him except two (albeit by a few weeks in some cases).

This is all fantastic news for the Detroit Pistons. They have a star on their hands. But to become a superduperstar, Cunningham has two last warts to freeze off. Both require a little context.

Everyone’s heard about Cunningham’s turnover problems at this point. He leads the league with 4.6 per game, a smidge higher than Young or Ball. Part of that is due to the sheer amount of playmaking that falls on the youngster. His actual turnover rate of 15.6% is only 34th percentile for point guards; in other words, below-average but far from league-worst.

My eyeballs see two major causes. First, he has to tighten up his handle. Cunningham’s ballhandling skill is high, but he can get careless with the rock. A low point was a recent game against the Pacers (an easy Detroit win, to be fair), when Jarace Walker snatched Cade’s cookies four separate times. He starts his crossover high and pushes through it slowly, giving good defenders time to jam him up:

Cunningham also routinely makes passes my toddler would call “silly” (and I’d call something else). At times, he predetermines his reads and can’t or won’t audible. His 8.3% turnover rate on drives is the highest of anyone in the top 20 for drives per game (min. 10 games played), and inexplicable passes like this are part of the reason why:

Other times, he gets caught indecisively in the air, lofting balloons for opponents to snag by the string and merrily sprint away with:

Cunningham should outgrow some of these mistakes, but like any high-usage ballhandler, some will always remain. Turnovers, in and of themselves, aren’t always a bad thing, but I’d like to see more turnovers of aggression rather than meekness. He needs to excise the worst offenses to maximize his playmaking abilities. I am optimistic he will do so, particularly as the Pistons’ surrounding cast improves.

Cade’s second flaw is a little more nuanced. He’s struggled to finish at the hoop his entire career, and it hasn’t improved much over time. A third of his shots have come at the rack this season, a substantial number, but Cunningham has never finished a season above 58% at the rim, an atrocious rate for a player his size.

A deeper statistical analysis reveals something interesting. Bball-Index’s proprietary formulas say Cunningham has elite finishing talent but is taking some of the hardest shots in the league when considering shot location and defensive presence (he is in the first percentile for “Rim Shot Quality”).

That’s a double-edged sword. On the one hand, it means Cade can generate and finish the difficult shots that all offenses require to a degree; on the other, it means he pretty much only takes difficult shots. Cade is a below-average athlete for someone who drives as much as he does, relying on craft and guile to worm into the paint. I’m not sure I’ve ever seen Cunningham redline his engine. The ability to play at his own pace is a skill, but he also never gets the blow-by layups that quicker counterparts can feast on.

He doesn’t have enough first-step quickness to explode past guys or vertical pop to elevate in traffic for big finishes (Cunningham has tallied just four dunks in 22 games this season). He is at his best when he remembers to use his size to bump a defender off their lane and extend over them for a layup. He loves to use a spin (full or half) to get a moment’s separation:

Taller, slower point guards rarely excel in the paint; LaMelo and Lonzo Ball have famously struggled with the same issue. Cunningham isn’t likely to turn into the Roadrunner anytime soon, but there are ways for him to improve.

Can he get even stronger and bully smaller defenders? Cade doesn’t have a bulldog frame, but there is potential for him to fill out more. Can his three-point accuracy improve to the point that defenders have to stick tighter to him, allowing him to create bigger advantages with hesitations and shot fakes? Can he develop Shai Gilgeous-Alexander’s airtight shake-and-bake handle? He’s been on-ball more than ever this year, but is there some latent cutting and off-ball savvy in his game? Cunningham’s also still working on his off-hand; he’s become far better driving left, but there’s still room for improvement.

A related note: finding a way to draw more free throws would help Cunningham’s efficiency immensely. Some Pistons fans believe he gets a bad whistle, but the truth is that he hasn’t been able to create off-the-dribble advantages that lead to compromised defenders. They have no reason to foul when they can bother the shot with a good contest.

Taking a step back, the fact that Cunningham can get to the rim as much as he does is promising; just a little more efficiency here would do wonders for his overall game. He’ll have to hit on at least one of the ideas above to do so.

The difference between stars and superstars is their ability to create high-level, efficient offense for themselves and their teammates. Cunningham has continually progressed in this area, and lineups with the point guard have scored at league-median rates despite below-average surrounding talent. But there isn’t a superstar in the league with as poor finishing numbers as Cunningham (at least, who doesn’t also draw free throws), and he simply must find a way to improve his rim scoring to reach his potential.

Cunningham has developed (and brought Detroit along with him) despite one of the worst basketball ecosystems in the league. For the first time since Cunningham was still in high school, the Pistons are respectably bad instead of a laughingstock (their best record in the last five years was 23-59; they’re on pace for 32 this season). Questions about Cunningham’s ceiling on a contender are beside the point; Cunningham is far from a finished product, and the Pistons have a lot of talent acquisition to go before they can start worrying about competing for home-court advantage in the playoffs. Cunningham has time and a clear roadmap for improvement. There are multiple routes he can travel to get to his destination, although he’s far from certain to get there. I’m excited to see which direction he takes.

![c63c5b14-f821-29d6-2b42-ed94a9aa84f3_1280x720.mp4 [optimize output image] c63c5b14-f821-29d6-2b42-ed94a9aa84f3_1280x720.mp4 [optimize output image]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!vzs9!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_lossy/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F4afec703-3c3e-4eb3-9aa4-82a07f171fb9_600x338.gif)

![b40900f1-62cb-cdcc-0c14-a69fcc8f6b0e_1280x720.mp4 [optimize output image] b40900f1-62cb-cdcc-0c14-a69fcc8f6b0e_1280x720.mp4 [optimize output image]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!B-u2!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_lossy/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fb101a4a1-2417-4d7a-b8cc-5f4c30c077d7_600x338.gif)

![jarace walker steal.mp4 [optimize output image] jarace walker steal.mp4 [optimize output image]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!Frrn!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_lossy/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F6791d7eb-03b0-4108-bb4b-9ccb983409ae_600x338.gif)

![pass out of bounds.mp4 [optimize output image] pass out of bounds.mp4 [optimize output image]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!eYH1!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_lossy/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F78c4a30a-47ac-4512-9ac6-14e988404354_600x338.gif)

![caught in air.mp4 [video-to-gif output image] caught in air.mp4 [video-to-gif output image]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!gpME!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_lossy/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F4e9dc4ac-d3ba-436c-8417-439da41d6893_600x338.gif)

![eeb463ac-5383-377b-f7f7-ab1158fe4d69_1280x720.mp4 [optimize output image] eeb463ac-5383-377b-f7f7-ab1158fe4d69_1280x720.mp4 [optimize output image]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!TdAY!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_lossy/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fcacc03d2-286c-402c-bea8-1c41ac8dcd3f_600x338.gif)

Quick correction: there are two players on the HNI younger than Cade: Sengun and Wembanyama.

"It’s a heavy load for a fourth-year player, particularly one still with fewer than two full seasons of games under his belt."

That right there points to what I think is the biggest part of Cade's current issues... besides his middling-by-NBA-standards athleticism, which he can only do so much to counter, all the court time he's missed due to injury so far in his career has slowed down his development. Well, that and the fact he now has a good coach who actually gives a crap for the first time since he got drafted.