One-Trick Ponies Aren't Extinct Yet

But they will be once general managers get on the same page as coaches

It used to be that if you had one plus skill, you could be a role player in the NBA. Think sweet-shooting but sedentary power forward Steve Novak, on-ball defensive menace Tony Allen, or shotblocking extraordinaire “Vanilla Gorilla” Joel Przybilla1. These guys all did one thing really, really well, and nothing else at even an adequate level, but that was ok! As recently as 2013, NBA front offices viewed specialists as a good thing.

Back then, it was easier to highlight players’ strengths while covering up their deficiencies. But styles and coaching schemes have evolved, and with the added luxury of time off, playoff offenses and defenses can completely change to attack an opponent’s weakest link.

It’s become increasingly clear that players must be at least minimally competent on both sides of the ball to get any playoff burn, or coaches won’t hesitate to yank them in high-leverage moments.

The death of the defensive specialist has a date: May 11, 2015. That day forever changed the course of the NBA, although we didn’t know it at the time, as that’s when rookie coach Steve Kerr made a tweak in his defensive scheme to help the talented-but-unproven Warriors tie up a second-round series against the grizzled Grizzlies, who had shocked the favored Warriors by roughhousing them into submission through the first three games.

The aforementioned Tony Allen had been everywhere in Games 1-3, locking up Klay Thompson and disrupting much of Golden State’s perimeter actions. He’d never been a massive scoring presence, but that wasn’t his role. Any offense from the All-Defensive First Teamer was a bonus, as far as the Grizzlies were concerned.

But Steve Kerr had a plan to get rid of the pesky Allen. To start Game 4, Kerr had his mammoth center, Andrew Bogut, defend Allen, a shooting guard, instead of the Grizzlies’ twin towers, Marc Gasol and Zach Randolph. However, that really meant that Bogut kept his giant butt right next to the hoop, completely ignoring Allen (stationed out on the perimeter) and mucking up the offense for the rest of the Grizz.

The Grizzlies, caught off guard, naturally tried passing to Allen. He bricked a few jumpers without a defender anywhere near him, and Memphis was forced to pull him from the game. The Warriors continued that strategy of ignoring the toothless Allen whenever he entered for the rest of the series, and the Grizzlies were utterly unable to score with him on the court. After playing 38, 37, and 33 minutes in Games 1-3, Allen clocked just 16 minutes in Game 4, didn’t play at all in Game 5, and just 5 minutes in Game 6. It goes without saying that the Warriors steamrolled the Grizzlies the rest of the way en route to their first championship (ignoring another defense-only wing, Andre Roberson, in the very next round).

That tweak may seem obvious to us now, but it was considered revolutionary back then. In the olden days, zone defense wasn’t allowed, and by rule, defenders had to guard even the worst shooters on the perimeter. The floor was automatically spaced because defenders had much less ability to dig into the paint or play help defense. The allowance of zone before the 2002 season technically would have allowed the Allen gambit much earlier, but it took time for players and coaches to mentally adjust to purposefully leaving an NBA player wide open.

After that series, teams all around the league became much more aggressive in ignoring defensive specialists. Defenders have tried to respond by developing just enough offensive juice to stay relevant (usually by hitting corner three-pointers), to varying degrees of success. There’s no room for useless statues when going up against a playoff-caliber defense with time to gameplan for your weaknesses.

Defensive studs who can’t play offense have been continually phased out of rotations ever since. Philadelphia’s Matisse Thybulle is one of the most incredible ballhawks I’ve ever seen. But his inability to even dribble a basketball, much less shoot one, has turned him into a bench paperweight in the playoffs, as we discussed before. Roberson couldn’t make a roster last season. Kris Dunn’s career might be dunn.

Similarly, the shooter specialist has died out, although it wasn’t quite so dramatic. Being a shooting “specialist” is a nice way of saying that a player sucks at everything else. Of course, shooting always has value, but if the specialist can’t play a certain bare minimum of defense, they now get relentlessly attacked to the point that their defensive deficiencies outweigh any offensive benefits they bring. Just ask Miami how they feel about Duncan Robinson right now, the $90 million man who racked up DNP-CDs in the playoffs. Or quiz Washington on their feelings towards Davis Bertans’ $80 million contract, which he rewarded by playing 14 minutes per game last year before they jettisoned him to Dallas as salary filler in the Kristaps Porziņģis trade.

If you want to be on the court as a shooting specialist, you can’t just be good. You can’t even be great. Hell, being historically dominant like Buddy Hield might not even be enough. Hield signed a $86 million contract three years ago, and yet, for all his shooting prowess, he has never made the playoffs — never sniffed them, if we’re being honest.

When will teams learn?

Jabari Parker knew the market realities. “They don’t pay players to play defense,” Jabari said back in 2018, and you only have to look at some of the contracts being handed out these days to see the veracity of that statement.

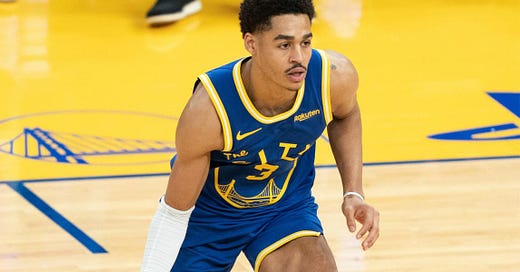

Anfernee Simons is one of the worst defensive players in the league, but he just got a $100 million contract. Opposing offenses habitually target Tyler Herro, but he just got $120 million (they’ll say $130 million, but it’s a lie). Jordan Poole shot incredibly in the playoffs but saw his playing time diminish as the stakes increased. He will get Herro-level money, as well. That’s a lot of moolah for a guy who averaged fewer than 21 minutes per game in the Finals.

Let’s be clear. Elite offensive creation is the most valuable and rarest skill in the NBA, so it’s understandable that the league values it highly. All three players will help their teams win many regular season games, and it’s not like two-way elite scorers grow on trees. But when the playoffs come, all three will have trouble sticking on the court if they don’t increase their effort on D.

The NBA Finals featured the Celtics and Warriors running out loads of multifaceted players capable of high-level play on both ends, and if a player couldn’t cut it on one end, they were liable to ride the pine. Even Draymond Green, one of the best defensive players of all time and a genius passer, isn’t immune. He was so ineffective as a finisher and shooter that coach Kerr benched him near the end of a critical Game 4 in the Finals to gas up the offense, something that was a massive blow to Green’s ego but set a tone that he’d have to bring it on both ends.

I’m not sure when the market will recognize that paying nine figures for players who might not be playable at the highest levels is a bad idea, but we clearly haven’t gotten to that point yet. Self-congratulatory general managers get high on their own supply when they see a player they drafted score 20 points per game. There are some reasons for the profligacy, however.

Offense is more important than defense, and the dollars flow accordingly. Many believe that defensive aptitude is as much a matter of will as skill, and the hope is that some of these guys (particularly Poole, who has better physical gifts than Herro or Simons) will dial up their defensive intensity in the playoffs to the point where they aren’t an albatross. And a salary cap that is expected to skyrocket with a new television deal in the next couple of years mitigates some of the risks of overpaying an offensive player today. Herro and Simons also have leverage; their skillsets aren’t easily replaced on their respective teams. So in a vacuum, each of these deals may be defensible.

But there’s a disconnect between who is getting paid and who is getting played, and a reckoning is coming. Teams with championship aspirations can’t spend on players who can’t play in the playoffs. The one-way defender is on life support. The offense-only player is still reaping windfalls, but it won’t be long before smart GMs adapt or go the way of the dinosaur.

There are better examples than Przybilla, but I don’t get to bring up his sweet nickname often, so indulge me.