How have NBA positions changed?

(And how much do you love line graphs?)

The NBA has changed dramatically over the decades. We’ve all seen copious analysis on leaguewide trends. But I wanted to look at something I haven’t examined before: The evolution of each position individually.

Positions aren’t defined as rigorously as they once were, and many players slide between slots depending on lineups, opponents, and evolving tactics. But there is still a general set of responsibilities and expectations that come with being a point guard or a center or whatever. To that end, I wanted to examine how box score contributions have changed over time from each position.

Much love to Basketball-Reference, which assigns every player a traditional position each season and has per-possession data. Studying on a possession level eliminates some of the biases inherent to any era-spanning analysis, such as fluctuations in pace.

A decent rule of thumb is that a basketball game is 100 possessions, so I made all the charts on a per-75-possessions basis to normalize to numbers that roughly make sense for a starter’s playing time.1

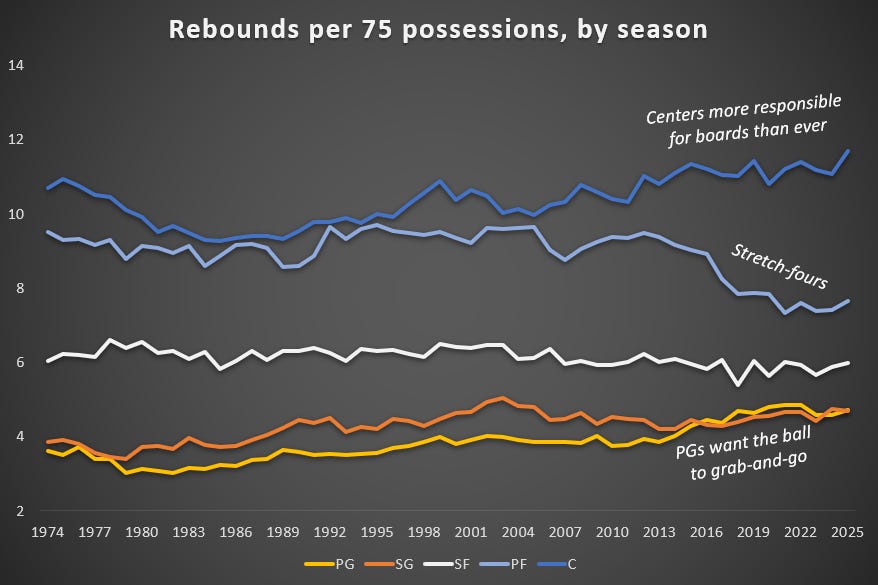

Enough with the boring stuff! To ease our way into this analysis, let’s look at how rebounds have changed over time.

The first thing that pops is obvious: The positions neatly sort themselves by height. Centers grab the most rebounds (nearly 12 per 75 possessions in the 2025 season, the highest ever recorded!), power forwards the second most, small forwards third-most, and guards the fewest.

But don’t let the obvious distract from a few interesting things.

First, we see the rise of the stretch-four happening here! Note the decline in PF rebounding that started in the early 2010s. As more power forwards began launching from deep, they started stationing themselves further away from the rim (both on offense and defense), limiting their chances for rebounds.

Centers, who are still generally kept around the basket, have actually seen their rebounds per possession increase in the same time span, as they’re often the only ones situated near the rim.

There’s also a bit of a rise in point guard rebounding of late. This chart should speak to the clear benefits of height for the purposes of retrieving an errant shot; incidentally, point guards are the only positional group that’s been getting taller. Also, modern point guards are encouraged to go get the dang ball themselves so that they can get into transition offense faster (one of the reasons why analytics folks didn’t mind Russell Westbrook “stealing” rebounds from Steven Adams back in his Thunder days).

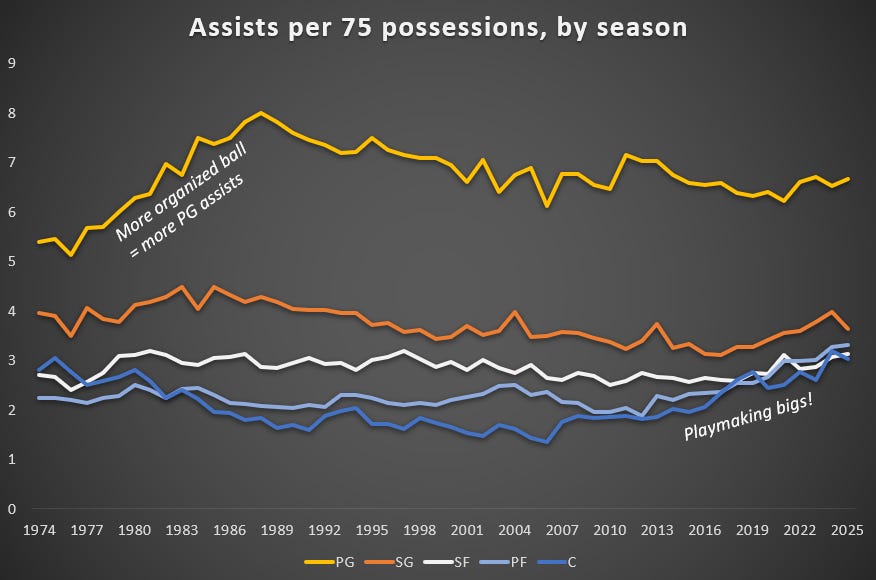

Like rebounds, assists have a subtle but interesting story to tell.

The most noteworthy thing is the big bounce in point guard assists from the ‘70s to the late ‘80s. The NBA game of the ‘70s was a fast-paced, run-and-gun affair, with relatively little half-court offensive organization and unsurprisingly inefficient shooting. As the game slowed, modernized, and became closer to the sport we see today, the point guard became a steadying organizational pillar with increased responsibilities.

There is also a belief that scorekeepers relaxed their interpretation of an assist over time. An assist is supposed to be a pass that leads directly to a score. Decades ago, almost any move by a shooter after receiving a pass would nullify the assist opportunity — or so the theory goes. While that’s probably true to an extent, it’s interesting that we don’t see a massive pop in assists per possession for any of the other positional groups over time.

The point guard remains the primary passer for most teams, but circa 2010, offenses started to recognize that more big men could and should be passing hubs, too. Think of this particular play below, commonly called “Delay,” in which the trailing big man becomes a playmaker from behind the three-point line:

Compare how many Delay variations happen on an average NBA team today (tons) to 25 years ago (relatively rarer). Even non-shooting bigs, like Jakob Poeltl in the clip above, can help space the floor if they are adept enough passers and screeners.

The non-PG positional parity in assist rates is a fun quirk of the modern NBA. Nikola Jokic is the ultimate proof that passing skill comes in all shapes and sizes, and coaches have become better at putting all players in the best place to maximize their skill sets. We are in the golden age of the passing big, both schematically and talent-wise.

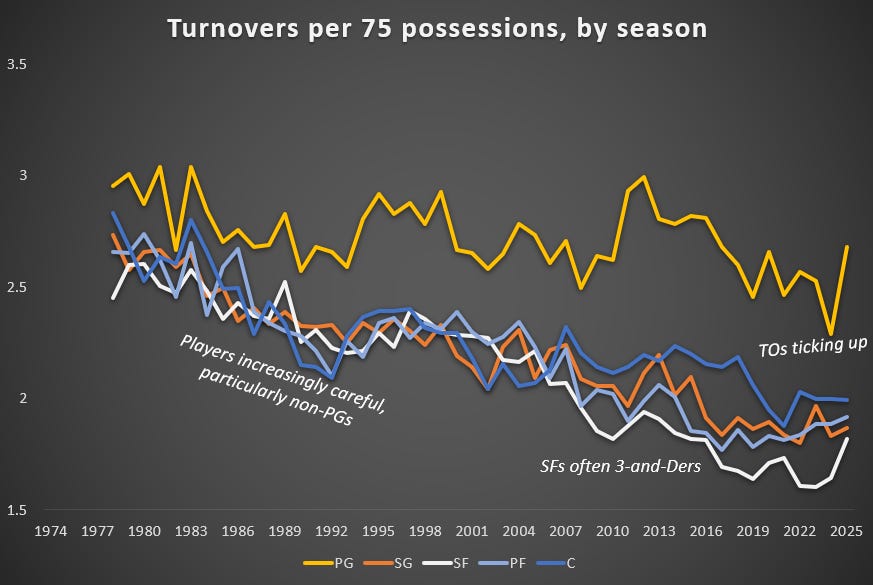

Turnover rate is another area where coaching and player evolution can be seen. Look at this:

Turnover rates are so much lower now than they’ve been in the last few decades.

SFs have seen the sharpest decline, largely because so many of them are 3(ish)-and-D(ish) specialists with limited ballhandling responsibilities. Point guards have seen the least decline, likely due to the increasing heliocentrism of the position, but every positional group has taken better care of the ball since the ‘70s and ‘80s.

Some of that is tied to the rise in three-pointers, as a player is far less likely to turn it over in the spacious acreage behind the arc than in the crowded phonebooth of the paint, but there’s also far greater awareness now of just how damaging turnovers are to a team’s chances of victory. (Decreasing turnovers is a prominent statistical phenomenon in the NFL, too.)

It is worth noting that turnovers actually ticked back up last season, even as the three-point rate continued to rise. I hypothesize that the increased frequency of transition possessions is the primary culprit, but there could be another reason I’m missing (all the injuries to stars putting more responsibility on players less equipped to handle it?). Samples are too small to determine causality at this point, anyway; it could easily just be a blip.

Alright, you made it! Now, we get to the good stuff: Scoring. Not coincidentally, it’s also the most interesting graph to look at.

![5b04bf93-0e43-b1b8-8bd3-bbe583d93fc0_1280x720.mp4 [optimize output image] 5b04bf93-0e43-b1b8-8bd3-bbe583d93fc0_1280x720.mp4 [optimize output image]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!GfQ3!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_lossy/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F79da649c-cf4c-48a7-b357-51f9b5920590_800x450.gif)